"A man ought to read just as inclination leads him, for what he reads as a task will do him little good."—Samuel Johnson

| Reviews | Limericks | Six Words | Buy Nothing |

11 November 2002

11 November 2002

Good in Bed

Jennifer Weiner

Sheila Levine is Alive and Living in Philadelphia

Weiner can't seem to make up her mind about what story she wants to tell aobut 28-year-old writer Candace Shapiro. Is this a goofy farce about a feisty reporter's encounters with celebrities? A psychological study of unrequited love and a woman's troubled relationship with her father? A wry commentary on being a large woman? A dark tale of violence and a child in jeopardy? A sweet urban romance? Weiner is at her best when she captures the way people really act, however harsh, such as when Cannie's grieving ex-boyfriend lures her into a sympathy shag during a shiva call. She's at her worst when she indulges in her fantasies about how people act: a movie star hunk is charmed when Cannie calls him anonymously on his cell phone; a screen diva runs into her in a bathroom and becomes her best friend and fairy godmother; her diet doctor turns into a stammering schoolboy when he meets the witty, zaftig Cannie. A book shouldn't have to be consistent or limited in tone or theme any more than life should, but the parts where Weiner coasts are a letdown compared to the parts where she pushes herself and tells it like it is.

Also by Weiner: Then Came You and Best Friends Forever

11 November 2002

11 November 2002

The Last American Man

Elizabeth Gilbert

While few books have truly changed my life, some, like this biography, have inspired me to seriously rethink it. Eustace Conway, born in North Carolina in 1961, has lived most of his life in the woods. Strong, graceful, a gifted horseman, he is good—even phenomenal—at everything he's ever tried. Driven since childhood by a belief that he is a Man of Destiny, he lectures tirelessly to schoolchildren and business people on how they can learn to live in harmony with nature and its physical laws, lessons no longer taught in modern American life. He wins admirers and inspires imitators with ease, but it breaks his heart to see how the young people who come eagerly to his camp don't even know how to hold a hammer. We have heard many times, and require little convincing of, his ideas about modern humans living in boxes with deadened souls, alienated from nature, in contrast to his cyclical, natural, authentic life. It is true that contemplating the life Eustace leads—growing or hunting everything he eats, sewing the buckskin he wears, constructing buildings without nails and doctoring animals on his own—leaves a typical modern American feeling thoroughly incompetent. Yet, while he has mastered life in nature, life with other human beings has not come easily to him. He is distant from his family, has few friends, drives away most of his worshipping disciples with his high expectations, and at the age of forty has never found the mate he desperately craves. Gilbert, a brilliant and funny writer, paints a complicated and compelling portrait of this larger-than-life figure. Eustace Conway may be behind his time, or he may be ahead of it; he may just be too much for this world.

Also by Gilbert: Stern Men and Committed

5 October 2002

5 October 2002

In the Little World: A True Story of Dwarfs, Love and Trouble

John H. Richardson

With so little written about dwarf culture, this book is welcome despite its flaws. Thankfully, Richardson doesn't take a feel-good approach, but he sometimes goes too far in the other direction, with no qualms about including unflattering physical descriptions of dwarfs. Much of the book consists of blow-by-blow e-mail fights between him and a female dwarf who takes him to task for his insensitivity. This does nothing but illustrate how men don't understand how hurtful their ideals of female beauty can be to women (“But we're just being honest!” they cry) and we didn't need to read any more about that. Another chunk of the book is about a family with a severely disabled dwarf daughter and a mother who's unraveling online trying to care for her, which ends up being more about the mother's borderline personality than anything to do with dwarfism. Also included are lousy photos that look like they were snapped without permission. Richardson doesn't make any claims to be anything other than a guy who's fascinated by dwarfs, but I wish he, or someone, would try a little harder.

5 October 2002

5 October 2002

Holy Days: The World of a Hasidic Family

Lis Harris

Harris spent several months visiting a Lubavitcher community in Brooklyn, joining their celebrations, eating meals with them, talking to them as much as she can. Their world is not easily penetrable, which makes Harris' accomplishment remarkable: while she doesn't shy away from the difficult (ugly clashes between the Lubavitchers and the Satmar, the strained lives of gay Orthodox men) she gives the reader a feel for the Hasidic way of life and a sense of its appeal.

5 October 2002

5 October 2002

The Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist, or How Every Culture Keeps Time Just a Little Bit Differently

Robert Levine

Everything you wanted to know about time but were too busy to ask. Psychologist Levine looks at time cross-culturally, at the relationship between time and power and between time and happiness, the history of timekeeping, and how long it takes to buy stamps in various American cities and what that tells you about the people living there. Some of the differences between cultures seem a bit oversimplified, although he also presents evidence, for example, that people in warmer places probably do have slower internal clocks, hence their slower pace of life. Also, obese people are more likely than average sized people to estimate the passage of time correctly. What implications this has, I don't know, but it's interesting reading.

4 May 2002

4 May 2002

The Dive From Clausen's Pier

Ann Packer

When I heard that the author of one of my favorite short story collections, Mendocino, had written a novel, I decided to read it without knowing anything more about it. It was a rare treat to plunge into something completely unknown. I won't be giving much away by saying that in the first few pages we meet a young woman, Carrie, who is engaged to her high school sweetheart but having second thoughts. When her fiancé dives into shallow water and becomes a quadriplegic, her restlessness takes on a new shape. Where it leads her I'll leave for you to find out. Carrie works in a library and has a passion for sewing, and Packer shares her protagonist's eye for color, shape and detail. Her characters, young people figuring out what they want to do with their lives and how they affect the people around them, are people you'll feel like you already know. This is a thoughtful, beautiful, and sad novel about love and responsibility, and how the choices we make are determined by—and determine—who we are.

22 February 2002

22 February 2002

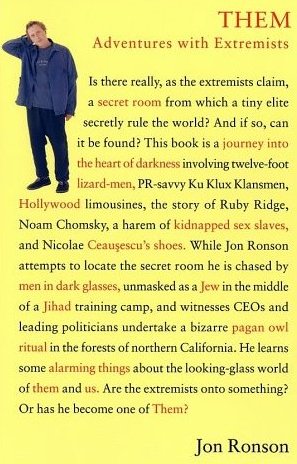

Them: Adventures with Extremists

Jon Ronson

Some books you read to be comforted, others to be shaken up. This is one of the latter. British journalist Jon Ronson follows around several colorful members of society's fringes, the ones who see a New World Order threatening their freedom or who spout hateful rhetoric that civil society likes to think is long extinct. But they're not quite what you might expect. What is one to make of the amiable Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan who reminds Ronson of Woody Allen? Or of a popular lecturer who truly believes that the world's leaders are directly descended from twelve-foot lizards? Or how about a right-wing talk radio host disguising himself as a preppy software developer in order to sneak into a bizarre forest ritual attended by some of the most powerful men in the world? It turns out that their paranoia isn't necessarily unjustified. As in the case of the FBI siege on the Weavers at Ruby Ridge, the government can be a threat to its people. This book reminds me of Julie Hecht's hilariously deadpan account of trailing the wacky Andy Kaufman, Was This Man a Genius?, except Them's funniness is discomforting because these guys are serious and potentially dangerous. The remarkable thing about Ronson's reporting is that no one comes off looking good, not even antiracist organizers or the Anti-Defamation League, and the reader's ideas about “us” and “them” are thrown into disarray. Is it scarier that, as Ronson discovers, there really is a powerful secret society promoting globalization—or that even they aren't in control of the world?

"There was so much to read, for one thing, and so much fine health to be pulled down out of the young breathgiving air...I was rather literary in college—one year I wrote a series of very solemn and obvious editorials for the Yale News—and now I was going to bring back all such things into my life and become again that most limited of all specialists, the 'well-rounded man.' This isn't just an epigram—life is much more successfully looked at from a single window, after all."—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Copyright © 1996–2026 So Much to Read

Contact: books at so much to read dot com